In my last post I wrote about how dreams have played a significant part in crucial decisions I have made in my life, how they gave me courage to pursue my aspirations, those other dreams.

Some people are so fragile that ridicule or disapproval is enough to make them doubt their own desires and instincts. All too often, especially in my younger years, I have been that kind of person.

So my dream of becoming a singer was put on hold for a while; put on hold but not put down completely. At least I stayed with music: I got both my bachelors and masters degrees in music. My BA is from some small liberal arts college or other; I also received a Masters in Vocal Accompanying and Coaching at the University of Illinois in Urbana, where I studied with John Wustman. My pianism was never more than a means of bringing me closer to singers; I was never terribly adroit technically, but through enormously hard work in those years with Wustman, I still managed to play some very difficult music: Wolf’s "Ich hab in Penna" from the

Italienisches Liederbuch (indeed the entire

Liederbuch), as well as his "Storchenbotschaft" and Tatyana’s Letter Scene from

Eugene Onegin. Those were probably the most difficult pieces I played, but in those years, I played about ten recitals every semester. It was intense, but it was also a very settled, happy time in my life.

Working with John Wustman changed my life completely. Observing a person who had dedicated his entire life to music, who had worked with the greatest singers in the world, who had strong and clearly formulated ideas about what made for great music-making, and who demanded that his students exceed their expectation of their own abilities. This last is how I managed to make it through that taxing repertoire. John reformulated everything that I thought I already knew about music, taught me how to make a real sound at the piano, and what legato was really all about. I left there with a more clearly defined sense of music in general and what kind of musician I was specifically.

But this all sounds so serious. The reason I learned so much from him is because he wasn’t all heavy and serious with me. He and I spent a significant amount of each lesson shooting the shit and cracking each other up. I heard more gossip about singers and it all made me feel like I was really a part of that world. Yes, he had an acerbic sense of humor (and still does), but I was never treated harshly in any way.

Immediately after getting my masters I went out to San Francisco, where I was an apprentice coach/accompanist in the Merola Program of the San Francisco Opera. Only in retrospect do I realize what an emotionally destabilizing experience that was for me. All of the administration and support staff remarked on what a friendly, well-adjusted, non-competitive batch of Merolini we were. What, in my great naiveté, did not realize, was that we were being observed and judged every second, and that the competition among some in our group was furtive, but no less harmful to someone like me, who had always lived in my own rarefied world, with no concern for or awareness of the political aspects of the world of music. The realization of this was shattering to me. I prefer not to dwell on the details of my disillusionment. I was green as they come when I arrived there and I left there no more worldly-wise but with no stars left in my eyes.

In spite of this, it was my intention to move to New York after I left San Francisco, and while I was in SF, I met the man with whom I would spend more than fifteen years of my life. That February I moved into his apartment in New York; in April we went to Italy together. I had been awarded a small study grant at the Merola Grand Finals which I used for a month of Italian study at the Universita per Stranieri in Perugia. Our first night in Perugia we stayed in a hotel, where we found that the word for double bed was "letto matrimoniale." We also learned that two young American men who requested such an amenity would not be accorded the highest regard.

The following morning we went to the administration building on campus to register and to arrange for housing. In those olden, pre-internet days, it was not possible to make such arrangements in advance, unless of course one sublet a fully-appointed private apartment, which was not financially viable for us. The administration building was sheer chaos, outside and in. The registration process involved going to at least three different rooms and by the time we left, we had our carte d’identita, but at what cost!

If the interior of the building was chaotic, upon exiting we encountered the sheer insanity such as only the Italians and the Greeks are able to sustain over time. Families with rooms to rent were supposed to register with the housing office, but more of them preferred to make arrangements themselves, perhaps to waive any fee the university might charge, or perhaps to simply have closer scrutiny over the foreign students they might house. My friend and I found it hard to get our bearings, so overwhelming was the scene, when suddenly a little Italian nonna appeared before us and asked "Lei cerca una camera?" Any wariness was offset by the thought of further administrative dealings, and the deal was cinched.

The nonna and her husband lived about ten minutes from that end of the campus. The charm of that walk is still present in my memory: thick tangled stems of wisteria just bursting into bloom, a church with a pair of beautiful bas-relief doors which N. later photographed. The house itself was very clean, but also very cold and dark. Our room at least had a large window looking out on a small patch of garden. The man of the house, the nonna’s husband, took particular pride in the bathroom, announcing as he turned on the taps in both sink and tub, "sempre acqua calda." We followed his lead and ran our fingers under the water, which at that moment was indeed hot. It was, however, the last time that month that hot water flowed from either tap.

Meals were not provided in the arrangement, but our tuition covered lunch and dinner in the student cafeteria, where the selections were less than stellar. The scariest selection was some scrawny variety of whitefish or other, always less than half-cooked, nearly unchewable, much less digestible. The safest bet was pasta con aglio ed olio.

On weekends, N and I traveled and explored other cities. Easter weekend, our first weekend there, we went to Roma, to St. Peter’s no less, and took in that whole spectacle, the ritual of the wizened, bent figure on the balcony, all in white. His voice echoed out over tinny loudspeakers as a rain just stronger than a drizzle fell in the piazza.

Another weekend we spent in Venezia, which enchanted me more than any other Italian city. Memories of the palazzo ducale, San Marco, Caff Florian, the vaporetti, the foul, intoxicating smell of the canals, are trumped for me the picture by a sheer curtain blowing in the window, set at an angle in the corner of our tiny hotel room.

A third weekend we took a trip to Firenze where the husband of N’s voice teacher was singing a lead role at the Maggio Musicale. On our other weekends away, we would return home on Sunday evening, but for a reason I no longer remember we stayed in Firenze an extra night, returning Monday morning. Having missed the first of our three daily classes at the Universita, we went straight "home" from the train station.

The moment we walked in the room, it was apparent that something was different. N said, someone’s been in this room, and I knew he was right. We were always suspicious that the nonna came into our room while we were out (which, alas, was void of a letto matrimoniale) and at first we thought this was what had happened. But no, after a few minutes, she came knocking on our door, which she rarely did, to tell us that the day before, she heard noise in our room and, entering the room, had surprised an intruder who was just escaping through the window into the garden. As far as she (or we) could tell, nothing had been taken, but a few things had been moved — what I noticed was the stuffed toucan named Tio that I used to travel with — and we could see where the window had been jimmied open.

That night I had the most vivid dream of my life. In real life, I had come out to my parents during my senior year of college; not surprisingly this had not gone terribly well. In the dream, they, distraught over my "self-avowed homosexuality" and my refusal to see a nice Christian "therapist" who would help me "change" were resorting to subterfuge: they had hired such a therapist who had agreed to examine me incognito. They would take me out for ice cream and she would pose as our waitress, which would enable her to evaluate the effects my godless lifestyle had already had on my soul, and the possibility of helping me turn back to Christ.

I can recreate the entire dreamscape in my mind: black and white tiles, sticky naugahyde booths, Wendy’s style lighting fixtures suspended from the ceiling, the attached fake cherry fan blades turning gently. And, dressed in a blue and white checkered waitress outfit, with a small frilly white apron, carrying a small order pad in one hand and the stub of pencil in the other hand, our "waitress" who had donned a curly blond wig perhaps to appear less formidable.

My parents, poor actors, were feigning such naturalness that even if it were not for the blond wig I would have known that something was up. The waitress was much more interested in the state of my soul than in what kind of ice cream I wanted. Instead of closing myself off, I decided to be honest with her. I told her everything: growing up knowing I was different, feeling isolated, facing incomprehension and judgment of everyone around me and finally, realizing that being gay was what had made me feel different all that time. And now that I finally knew who I was, I wouldn’t give that up for anything or anyone.

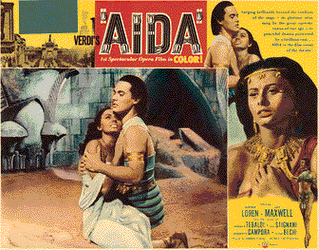

As I spoke, the shrink sat down in the booth opposite me – she had stopped taking notes on her order pad and was listening to me intently. When I finished, she said to me, is there anything you would like to say to your parents about all of this. I turned to them, tongue-tied upon seeing their angry faces. My mouth opened all by itself and a beautiful mezzo-soprano voice poured out. "Va, laisse couler mes larmes." "Let my tears flow, they do me good. The tears that one doesn’t cry fall inside our souls and hammer the sad and tired heart. The heart collapses and weakens, nothing can fill it and too fragile, it breaks."

As I sang, the sounds from my mouth turned into musical notes, which morphed into colors which wrapped themselves around me until I was bathed in a blue light. A bird flew up to me and settled on my outstretched hand. (Hey, it was a dream!)

When I finished, my parents were looking blankly at me, understanding nothing of what had just happened. But the waitress-shrink’s eyes were filled with tears. She turned to my parents and said, "There is nothing I can do for him, because there is nothing wrong with him."

My parents turned on her angrily, and launched a double-barreled attack on me. In spite of my best efforts, they remained in the dark. But someone else, someone who had been an adversary, had understood and had come to my defense. I began screaming and woke myself up in tears yelling, "There is nothing wrong with me, there is nothing wrong with me."

* * *

I am sitting at my desk, having just finished writing those last words and thinking to myself, this story is in two pieces. What does the first part have to do with that dream? My first inclination is to say, nothing whatsoever. That dream came from somewhere completely outside of me: it was a sign from a higher power about what would save my life.

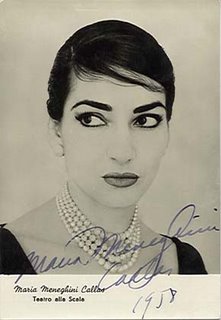

Another part of me says that this dream rose up from the deepest part of my unconscious, that in spite of everything, my inner self knew what message it needed to impart to me. All these prior events in my life had contributed to this hidden knowledge. Wandering through a foreign country, both literally and figuratively, trying to absorb everything around me, beginning a new life with someone I loved, living through a stressful summer in which I doubted my own abilities and nearly lost my love for music. And traveling even further back in time, beyond the Bubbles dream, beyond the Callas records, even beyond the

Victor Book of the Opera and that first record player, a little child whose mother would sing him to sleep with the lullaby "All Through the Night," a gift from my own mother who wasn’t even fully aware of what she was giving me.

Sleep my child, let peace attend thee,

All through the night.

Guardian angels God will send thee,

All through the night.

Soft the drowsy hours are creeping,

Hill and vale in slumber sleeping,

I my loving vigil keeping,

All through the night.