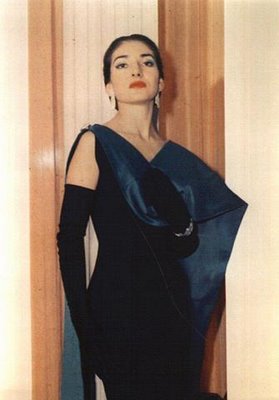

There is nothing I can add to the wealth of material that has been written on Callas (a large of amount of it pure trash, to be sure), so I won’t attempt any overreaching statements or opinions.

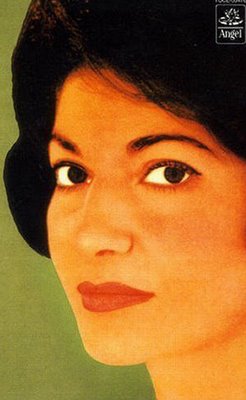

The most controversial singer of the last century (and perhaps also the greatest), her voice divided opinion from the very beginning, though her brilliant musicianship and theatrical sense were universally acknowledged. As I wrote a while back here, when I first heard her voice, I thought the LP was pressed off-center.

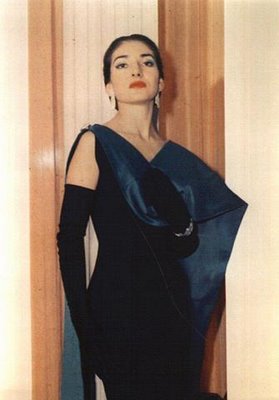

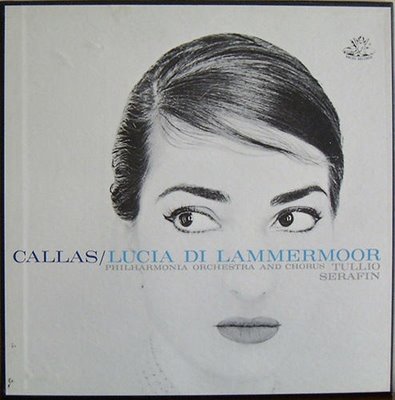

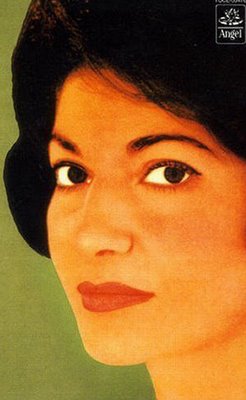

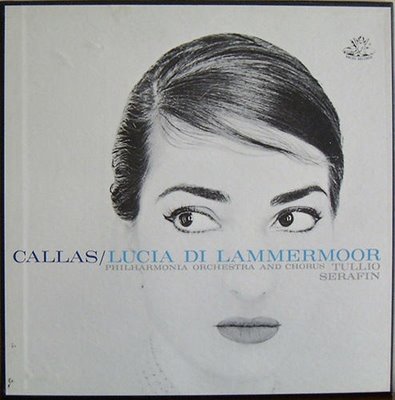

And yet she fascinated me nonetheless, even before I became a Callas freak (memorizing what she sang, where and when, collecting postcards, studying her recordings) – even before all of this, it was the eyes that haunted me: the cat eyes looking sideways, the hair pulled back, the lips preternaturally red on that otherwise all-white cover of the

Lucia stereo remake. That, and her strange, imperfect voice which wove itself around me. I found that there were people, some of them quite aware musically, who found it impossible to get beyond the peculiarities of the voice itself to the profound musical intelligence underneath. I have actually questioned my compatibility with friends and lovers who were not beguiled by Callas.

Of course it is because the voice was imperfect that she was compelled to make her mark in other, subtler ways. Tebaldi and Milanov, for example, possessed instantly recognizable voices as well, but neither one of those was allied with the musical genius of a Callas. Their voices were intrinsically beautiful in a way that Callas’ was not, but she dug deeper because she could not compete in that arena.

It was through her recording of “J’ai perdu mon Euridice” that I first ‘got’ Callas. She embodies Orphée in all his desperation with that instantly recognizable sound, plangent yet bottled. She makes ample use of chest voice, yet is infinitely subtle as well. The tenderness of “C’est ton époux” broke my heart over and over. I simply could not stop listening to this recording. There were other things on that recording of French Opera Heroines that I treasured (the Dalila in particular), yet it was this first cut that held me riveted.

One day in September 1977, my mother looked up from her newspaper and said, “you’ll never guess who died.” Without a single beat, I replied, “Callas.” And she asked if I had heard it on the radio and I said no, I could just tell from the tone in her voice. She didn’t believe me, but it was true.

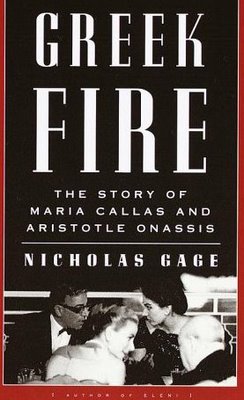

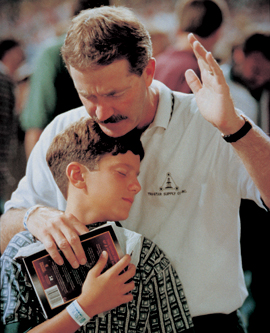

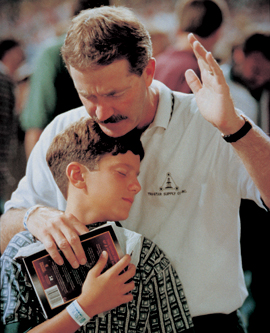

The next day, a Saturday, was a prayer retreat that I was obligated to attend. Genuinely bereft, if also just a touch melodramatic, I dressed quite ostentatiously all in black. No one else there showed the slightest grief over Callas’ death: those who had heard of her knew her only as Onassis’ mistress. My peers, out of earshot of their parents, referred to her as Maria Cow Ass.

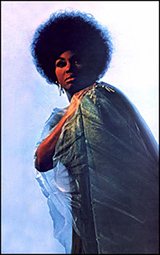

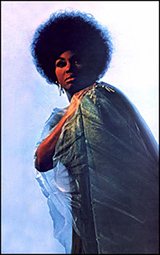

All those children of God, young and old alike, whether they knew who Callas was or not, were in agreement on one thing: my behavior was just more proof that Pastor Ted’s middle son was strange and most likely ungodly, concerning himself with matters that no “normal” Christian cared about. Didn’t the Greeks worship idols, after all? And what about that other opera singer that he was always going on about, that black woman with the big lips and the afro and the weird name?

I found solace alone in my room with Callas as Orphée, who sang of the utmost heartbreak in a melody which, though unremittingly in the major mode, yet conveyed the profoundest sense of alienation and loss.

Another iconic Callas recording for me is the Berlin

Lucia. The first time I heard this recording, it was Christmas break of my freshman year of college. My parents moved away from Oshkosh the day after I graduated from high school. I arranged to stay behind with a family from my father’s former church, since I already had two summer jobs lined up and, more significantly, did not want to say goodbye to my high school friends before it was time. So when I returned to Oshkosh at break, my visit had particular poignancy.

One person that I particularly wanted to see was my high school English teacher. In my junior year of high school I had been dangerously depressed: my family had moved a few months before, I had no friends, nor did I know how to make any. Unlike the people around me who should have noticed but were clueless, Gladys recognized that I was in trouble. She took me under her wing and I gradually gained confidence to step less fearfully, more confidently, into the big world beyond my father’s church. It is not exaggerating to say that in so doing, she saved my life.

So I went to Gladys’ on one memorable evening during my Christmas pilgrimage. A few other friends of Gladys’ were visiting, persons I had never met before, which made me a little uncomfortable. Conversation turned to the gift that Gail, Gladys’ daughter-in-law had given her: a live recording of

Lucia from Berlin, conducted by Karajan. I did not know the opera all that well, but I knew the mad scene, from the Sutherland recording that, a few years before, I had listened to and vocalized with

ad nauseum. Sure Dame Joan is vocally astounding, but with her garbled diction and a voice of a single color, she is a far cry from actually being Lucia. This was the first time I had ever heard a recording of Callas live, and it blew my mind. I was stunned by her daring tightrope walk through the omnipresent musical and vocal pitfalls. When she sang the words “il fantasma” I felt a surge run through my body. I held my breath during her first cadenza with the flute; my eyes rolled back into my head at her “Spargi d’amaro pianto”. By the time she sang that final E-flat, I was overwhelmed yet electrified; I could not even speak.

Gail made a joke about the performance causing me to have an orgasm, which deeply offended my still-puritanical tendencies. She was right, though at the time it didn’t feel like a sexual thing at all. When I lost my virginity nearly a year later, I realized that great singing and great sex evoked a remarkably similar response in me. In both cases, my life changed entirely over the course of a few short moments, relatively speaking. Maybe I really lost my virginity to Callas that night after all.

Labels: callas, countertenor, french opera, joan sutherland, losing virginity, lucia di lammermoor, milanov, orfeo ed euridice, orphee et euridice, tebaldi