Legendary Met broadcasts

Indisposed and confined at home today, I have been ripping and listening to a variety of music. The two standouts are broadcasts from the Met: a Trovatore from 1961 featuring Leontyne and Corelli coming just eight days after their legendary debuts in that house. The thrill of hearing these two in their respective primes is overwhelming.

Leontyne sings with such scrupulous musicianship and so much less whooping than one normally associates with her. The registers are more firmly knit, though she makes ample use of chest voice, and she does not use that awful measured trill in the last aria that she made such consistent use of almost immediately afterward. Her "D'amor" is by no means the finest I have ever heard from her: neither her ascent to the interpolated high D-flat in or the note itself is quite perfect, but it's still an impressive performance. In general, she is sometimes a little slovenly here and there, but the control of not only the cavatina of the the first act but the cabaletta in the first act aria is remarkable. I always found her handling of coloratura to be a little hit or miss, but she is more on top of it than I have ever heard before, both here and in the cabaletta to the Di Luna duet in the last act. At times she sounds a little at the edge of her resources by her attempts to shape the drama, but altogether, this is an exquisite documentation of an artist who, at her very best, was transcendent.

Leontyne sings with such scrupulous musicianship and so much less whooping than one normally associates with her. The registers are more firmly knit, though she makes ample use of chest voice, and she does not use that awful measured trill in the last aria that she made such consistent use of almost immediately afterward. Her "D'amor" is by no means the finest I have ever heard from her: neither her ascent to the interpolated high D-flat in or the note itself is quite perfect, but it's still an impressive performance. In general, she is sometimes a little slovenly here and there, but the control of not only the cavatina of the the first act but the cabaletta in the first act aria is remarkable. I always found her handling of coloratura to be a little hit or miss, but she is more on top of it than I have ever heard before, both here and in the cabaletta to the Di Luna duet in the last act. At times she sounds a little at the edge of her resources by her attempts to shape the drama, but altogether, this is an exquisite documentation of an artist who, at her very best, was transcendent.

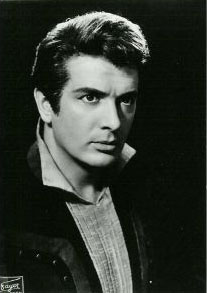

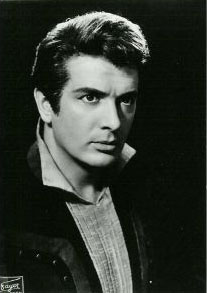

And Corelli: he is an animal, although he sings a very beautiful "Ah sì, ben mio" followed by a powerhouse "Di quella pira" (which, admittedly is down a half step, but who the f*ck cares. I have never heard a tenor who was particularly well-served by those shakes/trills in the vocal line of this aria; if the high notes come out gleamingly, then the performance is a success. But his singing of "Deserto sulla terra" and the "Miserere" are spot-on and while his mannerisms are also in evidence, anyone who loves Corelli has long ago accepted those quirks, that aggressive yet somehow assiduous musicianship that one hears (at least I do) in his bull-in-a-china-shop Roméo. Not to be vulgar or anything, but for me more than any other tenor, he sounds like sex on a stick. The high D-flat that he and Leontyne sustain at the end of the Act I trio is one of the most thrilling sounds I have ever heard.

And Corelli: he is an animal, although he sings a very beautiful "Ah sì, ben mio" followed by a powerhouse "Di quella pira" (which, admittedly is down a half step, but who the f*ck cares. I have never heard a tenor who was particularly well-served by those shakes/trills in the vocal line of this aria; if the high notes come out gleamingly, then the performance is a success. But his singing of "Deserto sulla terra" and the "Miserere" are spot-on and while his mannerisms are also in evidence, anyone who loves Corelli has long ago accepted those quirks, that aggressive yet somehow assiduous musicianship that one hears (at least I do) in his bull-in-a-china-shop Roméo. Not to be vulgar or anything, but for me more than any other tenor, he sounds like sex on a stick. The high D-flat that he and Leontyne sustain at the end of the Act I trio is one of the most thrilling sounds I have ever heard.

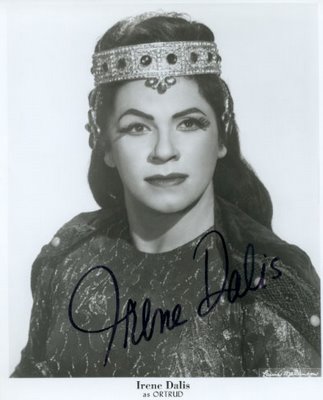

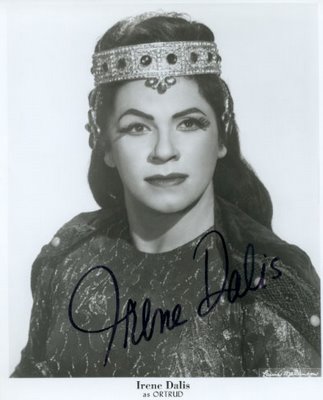

The other principals are Irene Dalis and Mario Sereni. Dalis sings her "Stride la vampa" quite cleanly, but she is somewhat wild dramatically: it's an odd dichotomy, and the audience affords her no applause after her aria. I confess I haven't listened to more of her performance, at least not yet.

The other principals are Irene Dalis and Mario Sereni. Dalis sings her "Stride la vampa" quite cleanly, but she is somewhat wild dramatically: it's an odd dichotomy, and the audience affords her no applause after her aria. I confess I haven't listened to more of her performance, at least not yet.

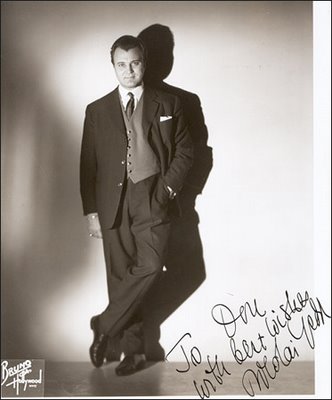

Mario Sereni was, in my opinion, an exceptionally good singer, and his work here is beyond reproach, and sometimes a good deal more than that. He deserved much more recognition as he deserves a permanent place in the collective memory of opera lovers. But alas, that doesn't happen nearly enough. How short people's memories are.

Mario Sereni was, in my opinion, an exceptionally good singer, and his work here is beyond reproach, and sometimes a good deal more than that. He deserved much more recognition as he deserves a permanent place in the collective memory of opera lovers. But alas, that doesn't happen nearly enough. How short people's memories are.

And Teresa Stratas is the Inez! She sounds very young and her Italian is not idiomatic, but she holds her own in her solo lines and it is quite clearly her!

And Teresa Stratas is the Inez! She sounds very young and her Italian is not idiomatic, but she holds her own in her solo lines and it is quite clearly her!

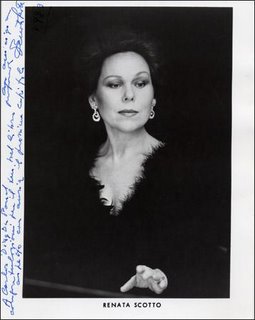

The other live Met recording I've been enjoying in snippets is a Vespri with Caballé from 1974. The supporting cast is not quite her equal, but she is supreme. All of her big moments, especially the first act scena and the "Arrigo" are breathtaking.

The other live Met recording I've been enjoying in snippets is a Vespri with Caballé from 1974. The supporting cast is not quite her equal, but she is supreme. All of her big moments, especially the first act scena and the "Arrigo" are breathtaking.

Gedda as Arrigo is better than I thought he would be. That is quite simply an impossible role, and he handles it as well as almost anyone else I have heard. Mind you, I only listened to excerpts.

Gedda as Arrigo is better than I thought he would be. That is quite simply an impossible role, and he handles it as well as almost anyone else I have heard. Mind you, I only listened to excerpts.

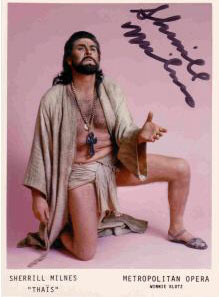

Sherrill Milnes can't hold a candle to Sereni. He is up to his usually vocal tricks, hooking up to his high notes with the most distorted and unpleasant vowels he can possibly summon. Funny that in the early years of their careers, he and Domingo were frequently paired; there was even an RCA issue of "Domingo Conducts Milnes; Milnes Conducts Domingo". Who would have predicted that the tenor would take up the baton more or less for real further down the line? And yet Milnes' star set very, very quickly. In my opinion he never lived up to his promise. Even in 1974 he sounds woolly and not terribly pleasant.

I have not yet listened to Justino Diaz as Procida.

But what a lovely way to spend a sick day!

Leontyne sings with such scrupulous musicianship and so much less whooping than one normally associates with her. The registers are more firmly knit, though she makes ample use of chest voice, and she does not use that awful measured trill in the last aria that she made such consistent use of almost immediately afterward. Her "D'amor" is by no means the finest I have ever heard from her: neither her ascent to the interpolated high D-flat in or the note itself is quite perfect, but it's still an impressive performance. In general, she is sometimes a little slovenly here and there, but the control of not only the cavatina of the the first act but the cabaletta in the first act aria is remarkable. I always found her handling of coloratura to be a little hit or miss, but she is more on top of it than I have ever heard before, both here and in the cabaletta to the Di Luna duet in the last act. At times she sounds a little at the edge of her resources by her attempts to shape the drama, but altogether, this is an exquisite documentation of an artist who, at her very best, was transcendent.

Leontyne sings with such scrupulous musicianship and so much less whooping than one normally associates with her. The registers are more firmly knit, though she makes ample use of chest voice, and she does not use that awful measured trill in the last aria that she made such consistent use of almost immediately afterward. Her "D'amor" is by no means the finest I have ever heard from her: neither her ascent to the interpolated high D-flat in or the note itself is quite perfect, but it's still an impressive performance. In general, she is sometimes a little slovenly here and there, but the control of not only the cavatina of the the first act but the cabaletta in the first act aria is remarkable. I always found her handling of coloratura to be a little hit or miss, but she is more on top of it than I have ever heard before, both here and in the cabaletta to the Di Luna duet in the last act. At times she sounds a little at the edge of her resources by her attempts to shape the drama, but altogether, this is an exquisite documentation of an artist who, at her very best, was transcendent. And Corelli: he is an animal, although he sings a very beautiful "Ah sì, ben mio" followed by a powerhouse "Di quella pira" (which, admittedly is down a half step, but who the f*ck cares. I have never heard a tenor who was particularly well-served by those shakes/trills in the vocal line of this aria; if the high notes come out gleamingly, then the performance is a success. But his singing of "Deserto sulla terra" and the "Miserere" are spot-on and while his mannerisms are also in evidence, anyone who loves Corelli has long ago accepted those quirks, that aggressive yet somehow assiduous musicianship that one hears (at least I do) in his bull-in-a-china-shop Roméo. Not to be vulgar or anything, but for me more than any other tenor, he sounds like sex on a stick. The high D-flat that he and Leontyne sustain at the end of the Act I trio is one of the most thrilling sounds I have ever heard.

And Corelli: he is an animal, although he sings a very beautiful "Ah sì, ben mio" followed by a powerhouse "Di quella pira" (which, admittedly is down a half step, but who the f*ck cares. I have never heard a tenor who was particularly well-served by those shakes/trills in the vocal line of this aria; if the high notes come out gleamingly, then the performance is a success. But his singing of "Deserto sulla terra" and the "Miserere" are spot-on and while his mannerisms are also in evidence, anyone who loves Corelli has long ago accepted those quirks, that aggressive yet somehow assiduous musicianship that one hears (at least I do) in his bull-in-a-china-shop Roméo. Not to be vulgar or anything, but for me more than any other tenor, he sounds like sex on a stick. The high D-flat that he and Leontyne sustain at the end of the Act I trio is one of the most thrilling sounds I have ever heard. The other principals are Irene Dalis and Mario Sereni. Dalis sings her "Stride la vampa" quite cleanly, but she is somewhat wild dramatically: it's an odd dichotomy, and the audience affords her no applause after her aria. I confess I haven't listened to more of her performance, at least not yet.

The other principals are Irene Dalis and Mario Sereni. Dalis sings her "Stride la vampa" quite cleanly, but she is somewhat wild dramatically: it's an odd dichotomy, and the audience affords her no applause after her aria. I confess I haven't listened to more of her performance, at least not yet. Mario Sereni was, in my opinion, an exceptionally good singer, and his work here is beyond reproach, and sometimes a good deal more than that. He deserved much more recognition as he deserves a permanent place in the collective memory of opera lovers. But alas, that doesn't happen nearly enough. How short people's memories are.

Mario Sereni was, in my opinion, an exceptionally good singer, and his work here is beyond reproach, and sometimes a good deal more than that. He deserved much more recognition as he deserves a permanent place in the collective memory of opera lovers. But alas, that doesn't happen nearly enough. How short people's memories are. And Teresa Stratas is the Inez! She sounds very young and her Italian is not idiomatic, but she holds her own in her solo lines and it is quite clearly her!

And Teresa Stratas is the Inez! She sounds very young and her Italian is not idiomatic, but she holds her own in her solo lines and it is quite clearly her! The other live Met recording I've been enjoying in snippets is a Vespri with Caballé from 1974. The supporting cast is not quite her equal, but she is supreme. All of her big moments, especially the first act scena and the "Arrigo" are breathtaking.

The other live Met recording I've been enjoying in snippets is a Vespri with Caballé from 1974. The supporting cast is not quite her equal, but she is supreme. All of her big moments, especially the first act scena and the "Arrigo" are breathtaking. Gedda as Arrigo is better than I thought he would be. That is quite simply an impossible role, and he handles it as well as almost anyone else I have heard. Mind you, I only listened to excerpts.

Gedda as Arrigo is better than I thought he would be. That is quite simply an impossible role, and he handles it as well as almost anyone else I have heard. Mind you, I only listened to excerpts.Sherrill Milnes can't hold a candle to Sereni. He is up to his usually vocal tricks, hooking up to his high notes with the most distorted and unpleasant vowels he can possibly summon. Funny that in the early years of their careers, he and Domingo were frequently paired; there was even an RCA issue of "Domingo Conducts Milnes; Milnes Conducts Domingo". Who would have predicted that the tenor would take up the baton more or less for real further down the line? And yet Milnes' star set very, very quickly. In my opinion he never lived up to his promise. Even in 1974 he sounds woolly and not terribly pleasant.

I have not yet listened to Justino Diaz as Procida.

But what a lovely way to spend a sick day!

Labels: franco corelli, leontyne price, mario sereni, montserrat caballe, sherrill milnes, trovatore, vespri