Herein follows Part Two of the Gundlach journey to singing:

In the next few years, my further exposure to opera was limited. I remember seeing part of a

Fledermaus on Public Television with a singer I learned later was Gundula Janowitz. When I turned ten years old, I was able to get a special stamp on my library card that allowed me to take out adult materials, including records. The first two records I checked out where an old Columbia pressing of the Opéra Comique version of

Les contes d’Hoffmann under Cluytens and the Boulez recording of

Pelléas. The Offenbach had no libretto, but the Pelléas had the original French and translations in English and German and Italian. I wouldn’t say that I quite faught myself conversational French in this way, but I sure as hell knew every word of Maeterlinck’s text. There were other recordings as well, particularly the Karajan

Zauberflöte with Seefried, Dermota, Kunz and Wilma Lipp. This youngster loved Kunz and Lipp the most.

At the age of twelve, I began to earn some money as the associate organist at my father’s church (the main organist took a rather active dislike to the pastor’s kid, a know-it-all, big-mouthed pre-fag). With the money I earned, I started to buy my own recordings. When my parents found out that I was buying recordings of Bartók (the “granddaddy of cacophony”) and

Wozzeck (the “devil’s tool”), I was cut off from buying any other recordings.

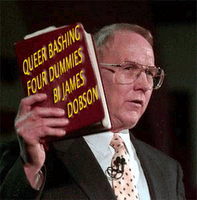

During this painful early adolescence, my parents sought to stave off the tell-tale signs of homosexuality by forcing me to join the junior high wrestling team.

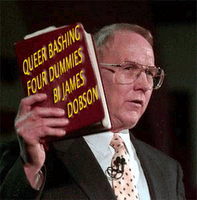

How grabbing at the shoulders, arms and thighs of my more generously muscled classmates was supposed to nip any latent homosexuality in the bug is beyond me. Actually, I believe it was advised by Dr. James Dobson in one of the books they took to heart.

After three excruciating and humiliating weeks of after-school practice, I finally quit the teams. I fled instead to the public library, returning home only after practice would have ended.

My mother, of course, found out from the meddlesome mother of a boy in our church who was also on the wrestling team, that I had quit the team. She arranged a surprise attack, coming to pick me up at school after wrestling practice and of course not finding me anywhere. When I was confronted with my perfidy, I could offer nothing in my defense except that I hated wrestling and didn’t want to be on the team in the first place. My punishment was to be grounded from music for six weeks: no records, either of my own or from the library, no radio, no piano lessons. My older brother, with whom I shared a room, reported me for lying on my bed with his clock radio (at the lowest possible volume) pressed to my ear.

Shortly thereafter I assigned myself the task of listening to every opera recording in the Oshkosh Public Library (to which city we had by now moved). This was the best-stocked library I had ever had access to, replete not just with recordings, but with piano-vocal scores as well, and I took full advantage. I made so many miraculous discoveries from the beginning. First was the Ludwig-Berry-Kertész recording of

Bluebeard’s Castle, which haunted me with its wealth of orchestral color and the peculiar inflections of the Hungarian language. There followed the first EMI Callas

Norma. I hated it; I checked to see if the recording had been pressed off-center, so ugly did her voice sound to me. Only after I heard her “J’ai perdu mon Euridice” (recorded when the voice was in much more precarious condition) did I finally “get” her. But even at first exposure it was clear that Callas as Norma left Sutherland completely in the dust.

Another pleasure from early in the alphabet was the Lear-Böhm recording of the two-act

Lulu torso (some baritone or other who shall remain nameless was Doktor Schön). The library had a vocal score of the opera as well, published only in German. Armed with an English singing translationof the libretty and an extremely fine-tipped pen, I wrote the entire English text above the printed German text.

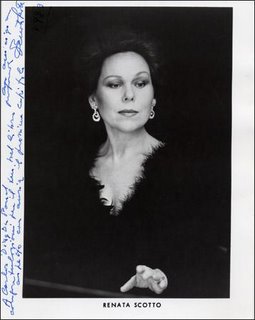

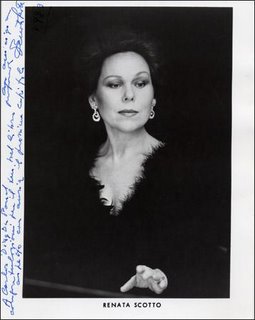

Around this time, I had a dream that changed my life. This was neither the first nor the last time this happened to me. There was a convention attended by all the world’s greatest singers and due to a last-minute emergency, it was being held in the basement of our house, in a half-finished room where I holed up for hours every day listening to records. It was my responsibility to make sure that the singers had enough to eat, so I was passing trays of canapés to Birgit Nilsson and Jon Vickers, too deep in conversation to even notice me. Martina Arroyo was there; I complimented her on her Ballo recording which I had just heard. Tatiana Troyanos was there, and Shirley Verrett, just transitioning into soprano rep. Scotto was primping in a mirror, admiring her new svelte figure. Even my adored Leontyne was there, but I was much too intimidated to even take the tray or hors d’oeuvres over to her, much less speak to her.

The master of ceremonies at this event was Beverly Sills, nearing the end of her “Bubbles” period, before she became the more formidable BEVERLY. I had borrowed one of those enormous coffee urns from the church, when Bubbles grabbed my arm and interrupted my duties. What are you doing, waiting on everyone, she asked. You’re supposed to be up here with us. When I found my tongue, I said, but I’ve never even studied voice, I barely know how to play the piano—and she cut me off. You don’t believe me now, she said, but you wait, and you’ll see that I’m right.

Though “only a dream” this pronouncement had a huge effect on me. No one in my family ever had exhibit such enthusiasm for or belief in my vocal talent. Perhaps this was unsurprising, since my only vocalizing consisted of me singing along at climactic phrases of arias as recorded by my favorite sopranos: Leontyne singing Thaïs’ Mirror Aria, Sutherland singing the final pages of the

Lucia mad scene, Janowitz singing “Ozean, du Ungeheuer,” Tebaldi singing Desdemonda’s “Ave Maria,” Scotto floating her magical pianissimi in the Canzone di Doretta. This was hardly a typical pastime for a red-blooded American boy; I had merely given up trying to make myself into something that I wasn’t.

A few weeks after I had had my Bubbles Dream, my parents asked if I intended to pursue music when I went to college. By “music” they meant my piano studies, so it came as rather a shock to them when I said to them, I’m going to become a singer. Their shock turned quickly to amusement: who are you kidding, they said, no one wants to hear you sing. And they laughed. It was an extremely hot and sticky summer evening and I went down to the basement and turned on the tap in the cinder block shower, and stuck my head under the water and cried.

But my wish wasn’t killed, just trodden underfoot. It took another dream twelve years later for me to finally realize that there was only one lot for me in life, and that was, after all, to be a singer.

Labels: autobiography, beverly sills, childhood, dreams, homosexuality, janowitz, leontyne price, opera, pelleas et melisande